This Family Was Responsible for Reviving a Style of Pottery-making First Used by the Tewa People.

Courtesy National Anthropological Archives, Smithsonian Establishment; neg. no. 1841-c.

In November 1992, "His" or Camille Nampeyo, a 28-year-old swell-great-granddaughter of the famous potter Nampeyo, was profiled equally one of two Hopi potters destined to carry on her ancestor's tradition (Jacka 1992). While women in the First Mesa villages on the Hopi reservation in northeastern Arizona have made pottery for trade or auction to the exterior world at least since the turn of the century, only in recent decades has some of it come up to be appreciated as American Indian art. Marketplace discourse uses linguistic communication such equally the "destiny" of named artists and the "approving of the Nampeyo family" This linguistic communication both constructs the value of Hopi pottery as art and obscures the social networks through which it is produced (Monthan and Monthan 1977; cf. Myers 1991).

I will evidence in this article how specific marketing practices take led to the genealogical reckoning of a Nampeyo "potter dynasty," now extended to five generations of potters subsequent to Nampeyo. This genealogical reckoning has been produced and canonized in various media from the stop of the 19th century to the present. Today, genealogies can be found prominently displayed with Hopi pottery for sale in shops as a guarantee of its authenticity. The canonization of the Nampeyo lineage in various media has structured the market for Hopi pottery in ways that create a demand for specific, named potters and item styles of piece of work. Furthermore, Western cultural values, which define objects equally art and isolate individuals as artists, work against local First Mesa values of producing social persons.

Potters and Traders (1890-1920)

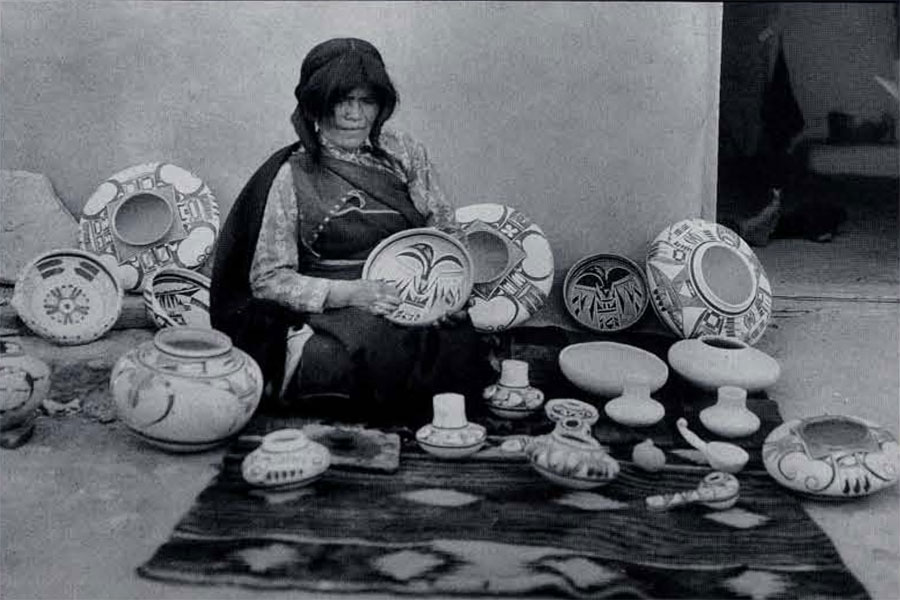

Decorated Hopi pottery of the 19th century was principally produced in the village of Walpi, the oldest Hopi village on Commencement Mesa (Figs. 2, iii). Nampeyo, the best known Outset Mesa potter of the 20th century, was built-in to a Tewa mother and a Hopi begetter around 1860 in Hanoki, or Hano, the hamlet settled in the late 17th century past Tewa immigrants from New United mexican states. Thus, Nampeyo and her matrilineal descendants are of Tewa descent. Yet they and their pottery have been identified consistently to the outside earth as Hopi. In the Hopi fashion of reckoning kinship, Nampeyo was built-in of her mother's Corn clan and built-in for her father's Ophidian clan. The women of her begetter's association gave her the name Nampeyo, which means Snake Girl or Harmless Snake. This is besides the proper noun with which she achieved her fame as a potter (Nequatewa 1943).

Nampeyo'southward paternal grandmother was a well-known potter from Walpi, and since her father ofttimes took her there, Nampeyo learned to make and specially to decorate pottery from her grandmother. By the time of Nampeyo'southward second marriage in 1881 to a Hopi man from Walpi named Lesou, she was already known as a good pottery designer using the "old Hopi" designs of that village (Nequatewa 1943).

As a young woman Nampeyo met and became familiar with white people. She kept firm for her brother, Tom Polacca, who supplied food and lodging for the 1875 Hayden Survey (Frisbie 1973:243). White people found her immediately intriguing. Struck by her beauty, William Henry Jackson, a member of the Survey, photographed her and created an image that became a pop representation of pueblo "maidens" (Fig. ane). This was the first of many photographs of Nampeyo taken by famous photographers and widely circulated to a public increasingly eager to acquire images and products of "ancient America."

In 1875 Thomas Keam opened the showtime trading post to serve the villages of First Mesa. Keam had a detail interest in pottery. He and his assistant, Alexander Stephen, explored local ruins and removed pots from them, especially from the ruin of Silcyatki where notable 15th and 16th century polychrome vessels were institute (Figs. 4, 5). Before 1890, Keam commissioned some First Mesa potters to make reproductions of Sikyatki vessels (Fig. half dozen; Wade and McChesney 1981:455). By 1895, Jesse Walter Fewkes was formally excavating the site for the Smithsonian Establishment, employing Nampeyo'due south hubby, Lesou, among other local men.

Courtesy Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology, Harvard University; cat. mo. 43-39-x/25890, neg. no. N31355. Photo by Hillel Burger. Ht. 22.0cm, Dia.27.0cm.

Through her associations with Keam and Fewkes, Nampeyo had both direct access to designs on pottery recovered from Silcyatki and encouragement to apply them. She readily adopted the style considering, according to Fewkes, she "found a ameliorate market for ancient than modern ware" (Stacey 1974a:37). Nampeyo instructed other Hano women in the new style; even so, her work surpassed theirs. Walpi women were disquisitional of Nampeyo and those she taught (Nequatewa 1943:89), a signal to which I will return.

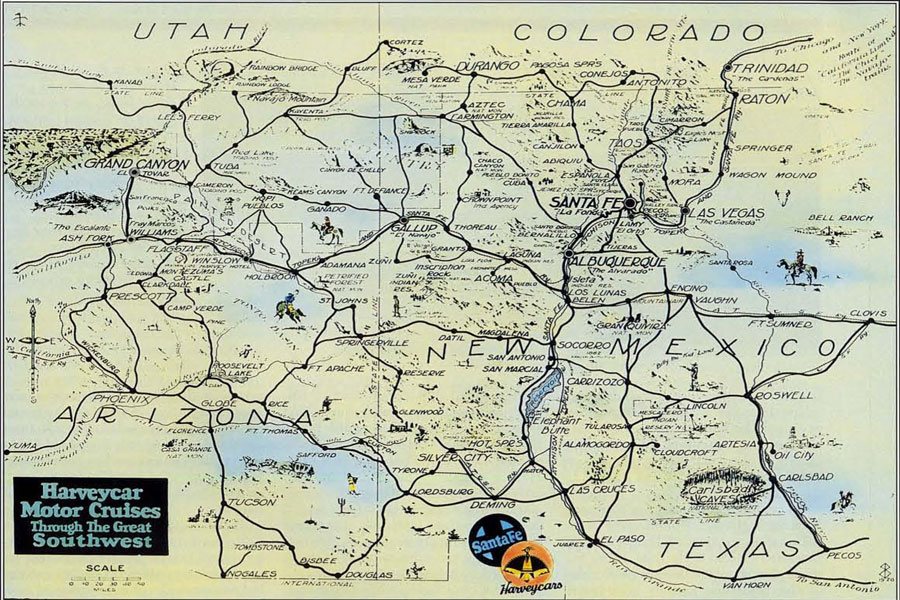

Whether or not Nampeyo was the sole potter decorating in the Sikyatki Revival style, and exactly when she switched from the "erstwhile Hopi" designs of Walpi to designs inspired past the pots recovered from Sikyatki (Fig. 7), are matters of some debate. What is meaning, notwithstanding, is that the Sikyatki Revival fashion of pottery decoration was an instant success with the traders, who bought information technology in large quantities and sold it to the outside world (Frisbie 1973:235; Nequatewa 1943:89). Traders such as the Hubbells and Tom Pavatea sometimes sold pottery directly to the public, but more oftentimes they sold wholesale to firms such equally the Fred Harvey Company, which operated a chain of restaurants serving the Santa Fe Railway and a tour service in the Southwest (Fig. eight).

Notable among the Harvey Company'south endeavors was a tourist allure called Hopi House side by side to the luxurious El Tovar Hotel at Grand Coulee (Figs. 9, x). Nampeyo was encouraged to demonstrate at Hopi House by John Lorenzo Hubbell, i of the traders to whom she sold or traded her work (Frisbie 1973, Kramer 1988). She starting time demonstrated in that location in 1905, a task that involved considerable logistics in temporarily relocating herself and 10 members of her family for 3 months. Amid those accompanying her were her married man, their two- or iii-year-old girl Fannie, their oldest daughter Annie Healing, and Annie'south husband and daughter Rachel, who was a year younger than Fannie (Kramer 1988:48-49). Nampeyo demonstrated at Hopi House once again in 1907. Pots which she produced there sold well and were marked with stickers, "Made by Nampeyo, Hopi."

In 1910, she again demonstrated pottery making, this time at Chicago's United States State and Irrigation Exposition, in a railway exhibit planned past George A. Dorsey of the Field Museum and Herman Schweizer, buyer and caput of the Indian Department for the Fred Harvey Company. Considering of her painting skill and the commercial success of this new decorative fashion, Nampeyo is widely credited with reviving the Hopi pottery tradition, which was then considered by scholars to exist in refuse.

Through her pottery-making demonstrations and widely distributed photographs of her taken past Curtis, Vroman, and photographers of the Harvey Visitor, Nampeyo became an icon of Hopi civilization. She came to symbolize not only its pottery, merely its people, and in the larger sense all that Hopi represented: the exotic and primitive, remote but domesticated American Southwest. In this fashion the proper nameNampeyobecame a tourist commodity. By the showtime decade of this century, Nampeyo's name was known throughout the United States and Europe, and every visitor to the Southwest brought dwelling a souvenir of her work (Hough 1915, Kramer 1988).

The result was that, although other First Mesa women connected to brand and sell pottery, some in the newly pop Sikyatki Revival style, Nampeyo's was the pottery most sought after.

The other potters' work didn't receive the attention maybe that Nampeyo did…; if they had had the opportunity to go to Grand Coulee and demonstrate, their name would have been on the forefront, too. But every bit it was Nampeyo got most of the credit because she was out there, simply one of those marketing things that happen. And and so when [tourists] came in [to trading posts in Keam's Coulee or Folacca], they would inquire for Nampeyo [pottery].Interview with William Bruce McGee, owner of McGees Beyond Native Tradition Gallery in Holbrook, Arizona, October 21,1992

The success of marketing named pottery was axiomatic.

Pride and Price in Art (1920-1960)

Courtesy Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology, Harvard University; cat. no. 43-39-ten/25129, neg. no. N33206. Photograph past Hillel Burger, Ht. 26.0 cm, Dia, 34.5 cm.

Courtesy Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology, Harvard University; cat. no. 43-39-10/25140, neg. no. N28794. Photograph by Hillel Burger. Ht. 24.3 cm, Dia. 34.5 cm.

With the inception of Santa Fe'due south Indian Market (1922), Gallup's Inter-Tribal Indian Formalism (1922), and the Museum of Northern Arizona'due south annual Hopi Craftsman exhibit (1930; see articles by Eaton and Westheimer, this issue), outlets for the sale of Indian handicrafts became more diversified. Marketing also became more restricted in the 1920s and 1930s, equally standards and criteria for the evaluation of Indian arts were established. Other fairs and exhibitions followed that became important outlets for Hopi pottery (Heard Museum Guild, 1955; Scottsdale National, 1961; Pueblo Grande, 1976), merely the first markets remained the virtually prestigious of the judging venues.

In the 1920s, with Nampeyo'southward eyesight failing but the demand for her pottery soaring, other members of the family unit painted for her, including her husband and her daughters Annie and Fannie. In fact, some First Mesa potters whom I take consulted claim that Lesou was the painter. Nampeyos encouraged her daughters to continue producing pottery as a style to make a living (Maxwell Museum 1974, Monthan and Montban 1977). Traders, as mediators between producers and consumers, too encouraged her offspring and in specific ways.

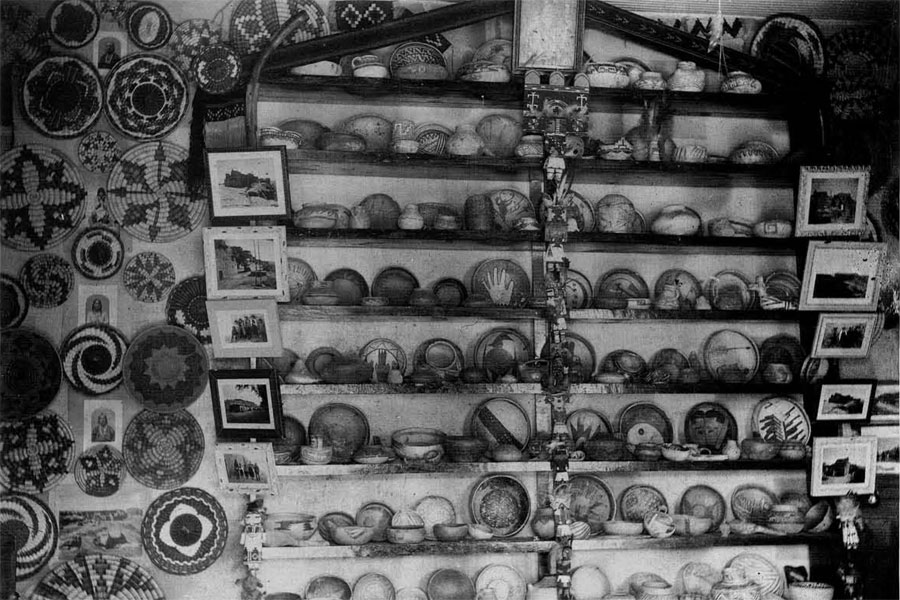

Traders connected to play an important office in the promotion of Indian crafts by selling pots wholesale to fairs and markets. They often served every bit "sponsors" for individual artists past signing works in pencil with the artist's name and conveying to the artists what kinds of objects won recognition in the form of ribbons and cash. Traders always provided prepare greenbacks or merchandise for objects. Potters could bring work at whatever time and non accept to await for fair dates, nor exist concerned about whether or non their work would sell at a off-white. This role of traders remains important fifty-fifty in today'southward market.

The period post-obit World State of war II saw the institutionalization of evaluative criteria for Indian art. Some consider that, as a result, pride of workmanship was achieved on a more widespread ground; members of Nampeyo'southward family unit, peculiarly Fannie, were already thought to take pride in their piece of work. Along with criteria of technical and aesthetic accomplishment came higher prices for works that met these criteria: thus an equivalence betwixt "excellence" and "cost" was established in the sale of Indian handicrafts.

"Generations in Dirt" (1960-1980)

(a) Driving from Holbrook n to the Hopi reservation, tourists encounter a sign for the original McGee family unit trading postal service in Keams Canyon, now named McGee and Sons.

(b) To suit tourists also as the reservation customs, the mail service, still owned by the McGees, has been converted to a complex including an Indian fine art gallery, restaurant, motel, gas station, and shopping center.

In 1938, the Keams Canyon trading post was taken over by the McGee family, who also purchased the Polacca shop from Tom Pavatea. The McGees continued buying from Nampeyos, especially Fannie who began signing pots "Fanny Nampeyo" post-obit her female parent's death in 1942. In 1947, the McGee family hired Byron Hunter to piece of work at their stores, at showtime during summers and in 1963 on a total-time ground at the Polacca store. A paved road to and across the Hopi reservation provided direct admission to Start Mesa, inducing greater tourist travel to the Hopi villages than had been achieved past railroad. Guidebooks (such every bit Hepburn's 1963Complete Guide to the Southwest)oriented tourists to the sights of the Southwest that were easily reached by auto, including its indigenous inhabitants. Byron Hunter continued to work with the Nampeyos, peculiarly Fannie and her daughters, critiquing the quality of the work they brought in, as did Bruce McGee who was trained by Byron Hunter.

In conjunction with guidebooks,Arizona Highways,a publication of the Arizona Department of Transportation, promoted tourism in the country. Bug featured photographic essays, in lavish color, of the landscape and its inhabitants. Beginning in 1960, the magazine produced special problems on Indian crafts. Along with coverage of prizes awarded at fairs and markets came profiles of individual artisans, their work (often photographed with a prize-winning ribbon), and the traders and galleries that represented them, including the Byron Hunter Trading Post and McGee'southward Indian Arts (Fig. xi). Photographs past Ray Manley and Jerry Jacka accompanied texts written past anthropologists, archaeologists, and museum personnel, too every bit staff writers.Arizona Highwaysbecame the primary medium for promoting the sale and consumption of items produced by Arizona Indians.

Past this time, buyers were differentiated into those purchasing curios and souvenirs and those seeking Indian art, i.due east., quality piece of work of specific artists equally defined past market outlets and publications. Nampeyo's pottery was divers as art, and due to the promotion she received "she was [known as] the greatest Indian pottery maker alive" (Kramer 1988:534). The steady supply of Nampeyo pottery was assured by both traders' encouragement of her offspring to "carry on the tradition" and by the media of tourism.

In 1974,Arizona Highwaysbegan a Collector Serial and produced two pottery issues, one on prehistoric and one on contemporary pottery. These problems were simply two examples of a profusion of such publications which appeared during that decade. The prehistoric pottery issue featured excerpts of Fewkes's Bureau of American Ethnology reports and a word of the beginning of the Sikyatki revival by Nampeyo (Stacey 1974a:36-37). The publication thus served to reify what was by now the myth that the revival resulted solely from Nampeyo'southward artistic talent. Although the contemporary pottery effect featured the piece of work of diverse Hopi potters, preeminent amidst them were "five potters and four generations of the Nampeyo family" (Stacey 1974b:20-21). The issue also included promotions for 2 forthcoming exhibits featuring Nampeyo and her descendants, 1 devoted exclusively to the Nampeyo family.

In the 1970s, exhibits devoted to the Nampeyos or featuring Nampeyo and her descendants were organized by museums or cultural centers (Museum of Northern Arizona 1973, Muckenthaler Cultural Eye 1974, Maxwell Museum 1974). Pottery by Nampeyo and from 16 to 27 of her descendants was included. These exhibits were often accompanied by catalogues that included genealogies of the Nampeyo family, both creating and demonstrating the continuation of this "pottery tradition" (Fig. 12; Collins 1974, Maxwell Museum 1974).

During this decade, the newest generation of potters included Hisi, who was 10 years erstwhile in 1974. The girl of Dextra Quotskuyva, Hisi is too the granddaughter of Annie and Willie Healing's daughter Rachel, who as a small kid accompanied Nampeyos on her first demonstration at Hopi Business firm. In turn, this was a period when Dextra herself was receiving considerable attention in the media, including recognition in the collector'due south issue ofArizona Highways(Stacey 1974b) and a profile inAmerican IndianFine art (Monthan and Monthan 1977). Thus, this new generation of creative person-potters was composed of the offspring of the first potter to produce a commodity for public consumption, now defined as an art form.

Hisi, and so, was socialized into the practices and institutions of marketing pottery from the outset. By the 1970s, the marketing of pottery had become practiced business, with pots commanding "impressive prices" and receiving "recognition every bit works of art." With four generations of feel in market practices preceding and preparing her, it is not surprising that the offspring of a Nampeyo descendant whose own reputation equally an artist was well established would exist encouraged to "carry on the tradition."

The education of the public by various media fostered brand-name buying, and a "consumer-straight" tendency began: the consumer/collector could go directly to the source, that is, the potter, without the arbitration of a trader. Nevertheless, traders were nonetheless actively structuring the marketplace. Any member of the family who wanted to make pottery was encouraged to do so, and Nampeyo pottery began to saturate the marketplace. Past 1983, 45 Nampeyo potters were featured in an exhibit held, significantly, in an Albuquerque gallery, rather than an anthropology museum. Hisi was among them. Past now she was nearly xx years erstwhile.

This exhibit catalogue's genealogy lists 64 Nampeyo descendants and affines (persons related by wedlock), including the offspring of Nampeyo's male descendants (notably those of Tom Polacca, Fannie's son) along with the offspring of her female descendants (Anthony 1983). The market was recognizing descent indiscriminately, that is, according to Euro-American bilateral rather than Hopi matrilineal criteria. Fifty-fifty male person relatives by marriage were encouraged to make and sell pottery.

What's in a Name? (1980-1990)

The Nampeyo dynasty of potters has been critically evaluated and shaped by dealers and the media during the last decade. Gallery x in Scottsdale, for example, an elite gallery with branches in New York Metropolis and Santa Fe, instituted annual Hopi shows in 1984 (Fig. xiii). In 1986 the gallery mounted a serial of exhibits defining new trends in Native American fine art which included Hopi pottery ("Treasures of the Western Native Americans," "All That's Really Worthwhile in American Indian Art," "Images from the Hopi Mesas," "A Calendar month of Anaesthesia"). In these exhibits only certain members of the Nampeyo family were featured, notably Dextra and Camille (Hisi) Quotskuyva and Tom, Gary, and Carla Folacca, forth with other Hopi artists. In the aforementioned year,Arizona Highwaysreleased its "New Individualists" issue, profiling Dextra and Tom, forth with Rondina Huma, a Hopi-Tewa potter from Hano, and Al Quoyawayma (Jackal 1986).

While marketing strategies instituted past dealers and the media were encouraging specific Nampeyos potters to refine their work and to develop more individualized styles, the market was also opening upwardly to other potters. Many of these (such as Rondina Huma) had won prizes at Indian Market. Others, such as Helen Naha (Feather Adult female) and Joy Navasie (Frog Woman), both First Mesa potters of Tewa descent, had won prizes and were featured in tourist publications such asArizona HighwaysandRay Manley'due south Collecting Southwestern Indian Arts and crafts(1979). The Navasies and Nahas have begun to receive media attention and some genealogical reckoning (i.e., expectations for the side by side generation), just not to the extent of the Nampeyo family unit. It still remains the case that no other potters take received every bit much attention every bit Nampeyo and her offspring. A significant contempo publication promoting the work of individual artists features the work of five living Nampeyos, two deceased Nampeyos, and 4 other Hopi potters (Jacka 1988).

The primary means for potters to develop their names equally artists and to have collectors seek out their work is to have it published in a "book" (i.eastward., photographed in ArizonaHighwaysor appearing in a gallery advertizing inAmerican Indian Art).The person responsible for accomplishing this kind of publication is the dealer. Prize winning, of course, is another important means of achieving recognition. Both work together to create and build an individual'southward name as an artist in the market.

The Work of Pottery Production and Social Recognition

The work of condign a named artist is not easy, as information technology involves social networks and values from differing cultural systems that often conflict. Many potters accept inadvertently severed relationships with dealers by complaining when they did not feel they received a "fair" price for their work, what they considered to be acceptable bounty, all the same ill-divers the concept. A dealer may feel that a showtime potter'south piece of work needs to starting time out at a lower level and be built upwards gradually through his efforts (dealers are principally male), establishing some consistency to the production. Dealers as well attempt to command the book of an private's piece of work in the marketplace at whatever given time, then every bit to build and keep its value loftier. Potters not familiar with these and other market place practices are frequently insulted past dealers who do not accede to their requests for pricing or other considerations.

Nampeyo was the outset Hopi potter to get a named artist. Her name was an identity given her by the women of her father'due south matrilineage as part of her larger social identity constructed through First Mesa kinship networks. Whether witting or non, in allowing this name to be commoditized and promoted she precluded recognition of the larger piece of work of pottery production that was recognized at Offset Mesa, peculiarly among the Hopi women of her father's matrilineage. At the time Nampeyo learned to brand pottery, potters worked collectively to produce their wares. Pottery thus objectified valued social relations where sharing with individuals not of one's matrilineage was both important and necessary for households to function. By engaging in social networks of a unlike cultural system with different values, Nampeyo'due south deportment negated the values of the First Mesa community. At First Mesa, broad kin networks are recognized in constructing social personhood (cf. Weiner 1976). Individuals have commented to me that pottery making did not belong to Nampeyo. She was non the first potter, and the women who taught her and her husband to pigment and shared their potting knowledge with them and contributed importantly to her work. This no doubt accounts in part for the criticism she received from Walpi women.

At Showtime Mesa the work of an individual, when it is recognized, is specific to that private and does not conduct through generations. Individuals decide for themselves when and how they will brainstorm to take upward pottery and use information technology for their living. Women (and now men) may encourage their daughters or sons, merely simply afterward these individuals take demonstrated their own interest in the work. This is true also for His, who, afterward becoming trained in estimator technology, decided to render to Get-go Mesa to make her living past pottery (Jackal 1992). Nevertheless, her decision was likewise encouraged past the social relations of the market, with which she is now fully familiar. She can and does claim the Nampeyo proper name. Just the "generations in clay" of which she has been selected to be the contemporary representative are a product of Western art market practices and soapbox.

Source: https://www.penn.museum/sites/expedition/producing-generations-in-clay/

0 Response to "This Family Was Responsible for Reviving a Style of Pottery-making First Used by the Tewa People."

Post a Comment